Study Suggests Three Mile Island Radiation May Have Injured People Living Near Reactor

CHAPEL HILL -- Exposure to high doses of radiation shortly after the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island may have increased cancer among Pennsylvanians downwind of the plant, scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill say.

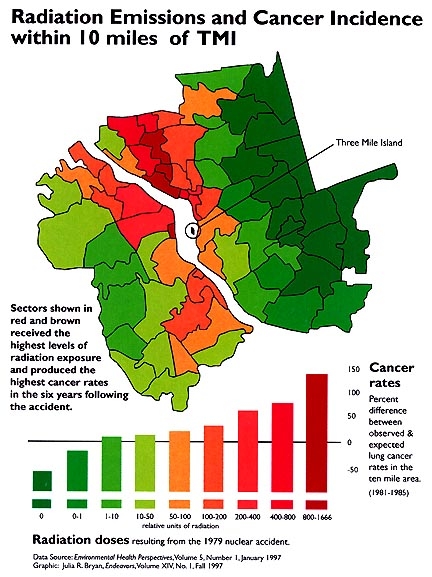

Dr. Steven Wing, associate professor of epidemiology at the UNC-CH School of Public Health, led a study of cancer cases within 10 miles of the facility from 1975 to 1985. He and colleagues conclude that following the March 28, 1979 accident, lung cancer and leukemia rates were two to 10 times higher downwind of the Three Mile Island (TMI) reactor than upwind.

A paper Wing and colleagues wrote appears in the January issue of the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, scheduled to appear Feb. 24. They first presented their findings last July at the University of Portsmouth in Portsmouth, United Kingdom, at the International Workshop on Radiation Exposures by Nuclear Facilities.

"I would be the first to say that our study doesn't prove by itself that there were high-level radiation exposures, but it is part of a body of evidence that is consistent with high exposures," Wing said. "The cancer findings, along with studies of animals, plants and chromosomal damage in Three Mile Island area residents, all point to much higher radiation levels than were previously reported. If you say that there was no high radiation, then you are left with higher cancer rates downwind of the plume that are otherwise unexplainable."

Co-authors of the report are Dr. Douglas Crawford-Brown, professor of environmental sciences and engineering, and Dr. Donna Armstrong and David Richardson, former and current doctoral students in epidemiology, all at UNC-CH.

The new study involved re-analyzing data from a 1990 report that concluded the nation's worst civilian nuclear accident was not responsible for slightly increased cancer rates near the plant because radiation exposures were too low. Wing and colleagues re-examined data from that report using what they believed were better analytic and statistical techniques.

"Several hundred people at the time of the accident reported nausea, vomiting, hair loss and skin rashes, and a number said their pets died or had symptoms of radiation exposure," he said. "We figured that if that were possible, we ought to look at it again. After adjusting for pre-accident cancer incidence, we found a striking increase in cancers downwind from Three Mile Island."

The scientists do not believe smoking and social and economic factors were responsible for the increased cancers found in the downwind sectors.

Many earlier researchers, as well as government and industry officials, accept as fact that only small amounts of radiation were released into the atmosphere, Wing said. But it is known that plant radiation monitors went off scale when the accident started. Plumes containing higher radiation could have passed undetected, he said.

Findings from the re-analysis of cancer incidence around TMI is consistent with the theory that radiation from the accident increased cancer in areas that were in the path of radioactive plumes, the scientist said.

"This cancer increase would not be expected to occur over a short time in the general population unless doses were far higher than estimated by industry and government authorities," Wing said. "Our findings support the allegation that the people who reported rashes, hair loss, vomiting and pet deaths after the accident were exposed to high level radiation and not only suffering from emotional stress."

The UNC-CH scientist said he found it ironic that U.S. District Court Judge Sylvia Rambo dismissed more than 2,000 damage claims filed against the power plant by nearby residents last year citing a "paucity of proof" to support their cases.

"Judge Rambo spent a year or more throwing out scientific evidence presented by the plaintiffs," he said. "After she threw out the evidence that people had been injured by the accident, including part of our work, then she ruled that there wasn't enough to proceed with the case."

He also noted that the court gave attorneys for the nuclear industry the right to review the earlier health effects research before it was made public. "I think our findings show there ought to be a more serious investigation of what happened after the Three Mile Island accident," Wing said.

Limitations of the new study, like the earlier work, include the continuing difficulty of determining precise wind direction for several days following the accident.

- Log in to post comments